Government mandated shutdowns of the Internet are becoming more systematic and more frequent. Access Now, a human rights group fighting for a free and open Internet said there were 56 Internet shutdowns across 18 countries in 2016, up from just 15 the previous year.

Most regions across the globe have seen Internet shutdowns lasting anywhere from a few hours to a weeks. Brazil, Malaysia, Algeria, Turkey, India, and North Korea all experienced at least one shutdown in the past two years.

“We first saw this as an issue during the Egypt uprising in early 2011 when telcos shut off all domestic access to the Internet,” noted Peter Micek, global policy and legal counsel for Access Now.

Governments use shutdowns for a variety of reasons, from stopping ‘fake news’ to prevent cheating on exams.

Execution

Governments vary the way they shutdown the Internet, ranging from limited blocks on certain social media websites to putting entire towns completely offline. Often, national security is the named reason by government authorities.

Julie Owono, head of the Africa desk at Internet Without Borders, notes that “most documented shutdowns occurred within an intense political context, be it contested elections or citizens protesting in the streets.” In Turkey during the months after the failed coup, users in the country faced repetitive blocks on social media outlets like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and WhatsApp.

Julie Owono, head of the Africa desk at Internet Without Borders, notes that “most documented shutdowns occurred within an intense political context, be it contested elections or citizens protesting in the streets.” In Turkey during the months after the failed coup, users in the country faced repetitive blocks on social media outlets like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and WhatsApp.

Governments themselves do not have access to a kill switch; they need telecom operators to be complicit. But this is easy via a court order or legal request, making a block list of select sites or shutting down certain locations possible. Telecoms providers are bound by national regulations and license agreements, so few choose to disobey the government.

However, telecom companies do have power as they can go to court, lobby government and peers to push back against orders – but this of course is affected by how authoritarian their governing regime is. Stockholm-based telecom Telia decided to promote transparency by publishing any problematic requests. The governments of Tajikistan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan are among those they’ve publicly exposed.

Cameroon’s example

On January 17 this year, Cameroon’s English-speaking regions were plunged into an Internet blackout which is still ongoing. This follows organised ‘ghost town’ strikes and street protests in 2016 after the Anglophone provinces felt marginalised by poor infrastructure and the government’s attempts to require the use of French in courts and schools.

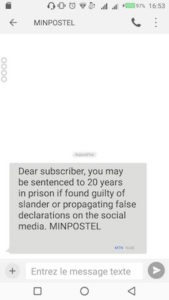

Before the shutdown, mobile users received warning texts from the Telecommunications Ministry stating that two years of jail time could be the result of publishing or sharing unverified news. “The government has been waging a war against social media, precisely because of its power to show how protesters are being treated and counter official government propaganda,” said Owono. Once the shutdown was in effect, SMS warnings upped the stakes to 20 years in prison.

Before the shutdown, mobile users received warning texts from the Telecommunications Ministry stating that two years of jail time could be the result of publishing or sharing unverified news. “The government has been waging a war against social media, precisely because of its power to show how protesters are being treated and counter official government propaganda,” said Owono. Once the shutdown was in effect, SMS warnings upped the stakes to 20 years in prison.

The result

Local businesses and access to education have suffered during the shutdown. Unrest has led to school closures meaning students have to travel long distances to different French-speaking regions in order to complete course virtually.

National human rights groups have reported arbitrary arrests since the shutdown started, often targeting protesters. David Kaye, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression called the shutdown a violation of international law and denying Cameroonians “access to essential services and basic resources.”

Students & businesses frustrated by internet shutdown in Buea. Some forced to travel to Douala for research.#BringBackOurInternet #Cameroon pic.twitter.com/z4IBhdbZVq

— Albert Nchinda (@AlbertNchinda) March 2, 2017

To get round it?

You have to use a VPN, which tricks the Internet Service Provider into thinking that you are using the Internet from a different location by changing your IP address so that it does not fall within the confines of the banned location.

But if the Internet is completely shutdown, then there is no workaround – and this has a huge economic impact. According to the Brookings Institution, nations who muzzled access to the Internet lost $2.4 billion in 2015.