If there was one Republican in Alabama the Democratic Doug Jones could beat, Roy Moore was that Republican.

And in a Tuesday night nail-biter, Jones did just that, edging Moore by a mere 1.5 percentage points in a state that hasn’t elected a Democrat to the U.S. Senate since 1992.

So while the Democrats are celebrating a victory in the special election, perhaps it makes sense to ask: How did Republicans manage to lose this seat?

So while the Democrats are celebrating a victory in the special election, perhaps it makes sense to ask: How did Republicans manage to lose this seat?

How we got here

Let’s take a moment simply to marvel at the bizarre and cumulatively improbable series of events that ever led us to a “Senator Jones.”

You could say it began in 2014. That’s when Dianne Bentley, wife of 50 years to Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley, a 71-year-old Baptist deacon, began to suspect her husband was having an affair with a member of his staff decades his junior. Dianne planted a recording device in the governor’s office and captured some intimate phone dialogue. The governor attempted to use state resources to cover up his affair. Dianne leaked her tape to the press and the controversy exploded.

Meanwhile, another scandal was brewing. Alabama Chief Justice and conservative firebrand, Roy Moore, was suspended from active service as a result of an ethics investigation stemming from orders he gave to the state’s 67 probate judges to disregard the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision legalizing same-sex marriage. This was, incredibly, the second time in his career that he had been removed from the bench for defying a federal court order.

Back in gubernatorial purgatory, pressure had mounted upon Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange to investigate Bentley. Strange, though, was in no hurry to do this. You see, while the Bentley scandal was unfolding, Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. Trump selected Alabama’s junior U.S. senator, Jeff Sessions, to become his attorney general, thereby creating a vacancy in the Senate.

In this vacancy, Gov. Bentley reportedly saw an opportunity to avoid prosecution. He could appoint Strange to Sessions’ vacated seat, then appoint a new – presumably more sympathetic – state attorney general to replace Strange, and avoid prosecution. Allegedly to facilitate this scheme, Strange sent a letter to the Alabama House of Representatives urging them to slow down on articles of impeachment. In February 2017, Bentley appointed Strange to Sessions’ vacant seat. The public screamed foul at the apparent corrupt bargain.

After nearly a year of ceaseless controversy, Bentley entered into a deal to plead guilty to two misdemeanors, resign the governorship and avoid a more aggressive prosecution. Alabama Lt. Gov. Kay Ivey assumed the office of governor and swiftly moved up the date of Strange’s election by more than a year. Seizing upon this opportunity, the suspended Roy Moore resigned the chief justiceship and announced his opposition to Strange. The race pitted President Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell on the side of Strange with Trump’s former campaign director Steve Bannon supporting Moore. Roy Moore trounced Strange by nearly 10 percentage points on his way to the general election.

But at least one more shoe needed to drop. Approximately one month before the election, the Washington Post published bombshell accusations that Moore had serially preyed upon teenagers as young as 14 when he was in his 30s. A flurry of accusations followed, with a total of nine women accusing Moore of some sort kind of sexual misconduct. Before they knew it, Republicans found themselves in a neck-and-neck race with Jones, a former federal district attorney most famous for successfully prosecuting a Klansman who bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church.

A steep hill for any Democrat

In an ordinary race, Jones would have been a severe underdog. His base, African-American voters, the young, urban, and the well-educated constitute only about 35 percent of the state’s electorate. Nevertheless, this was not an ordinary race.

Alabama’s Republican Party is predominantly composed of upper-middle class individuals and white evangelicals. Generally, they vote as an homogeneous group. But Roy Moore, like George Wallace before him, has been a perennially divisive figure. He vocally supports an agenda of Christian supremacy such as bringing back state-led school prayers, outlawing homosexuality and barring Muslims from serving in Congress.

Moore’s extremism makes wealthier and better-educated Republicans in Alabama’s cities and suburbs uneasy, but he remains the darling of the hinterland. Rural voters have largely disbelieved Moore’s accusers. They characterize these accusations as contrived attacks upon a man they deeply affiliate with, ginned up by enemies who care more about tipping the outcome of an election than in reporting matters of fact.

Moore’s unique unpopularity meant that, even before the scandal, Jones had a fighting chance. In Moore’s last election in 2012, he only narrowly beat Democrat Bob Vance for the chief justiceship – earning 52 percent of the vote compared to the 61 percent Mitt Romney earned the same day. Moore performed similarly yesterday compared to 2012 – even improving his performance in rural, overwhelmingly white counties. But his losses in more populous areas ultimately outweighed his strongholds.

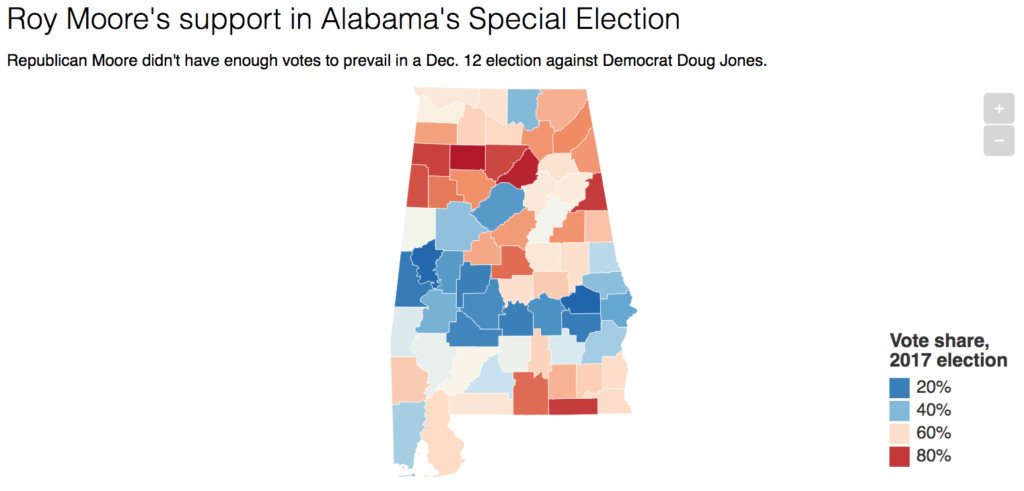

Jones, like most Democrats, ran up the score in the cities and in the Black Belt – a swath of southern counties where a majority of voters are African-American. Moore did his best in the Wiregrass – counties near the Florida border – and in rural north Alabama. But when you compare Moore’s share of the vote with Donald Trump’s from last November, Moore’s numbers are worse in every single county.

Moore especially underperformed around the suburbs. In Shelby and Tuscaloosa Counties, located south and west of Birmingham, Moore’s share of the vote was about 16 percentage points below what Trump earned last year. In more highly educated counties, such as Madison – home to a NASA research center – Moore also performed poorly compared to Trump.

Future of Alabama and Republican politics

Both the Alabama and national Republican Parties have some soul-searching to do. Roy Moore’s failed Senate bid demonstrates fundamental weaknesses for a political party with a narrow, and narrowing, base of power.

Right about now, Republicans are nervously eyeing their suburban base of support. In the 1970s and ‘80s, the Republican Party carved out one of the most durable coalitions in American political history using suburban voters as a springboard to public office. Last year’s presidential election and this year’s special elections demonstrate that Republicans are healthy in the hinterland, but Democrats are making important headway into the suburbs. As the Republican Party becomes the Party of Trump and Moore, the party that looks the other way on alleged sexual assault and pedophilia, a study from the Pew Research Center shows young, educated and wealthy voters leaving the party in droves.

The Alabama Republican Party has less to fear than their national counterpart, but if candidates like Moore continue to win Republican primaries, that may change. Trump won Alabama by nearly 30 percentage points, and Roy Moore is a unique candidate. But even in highly conservative Alabama, Republicans have a demographic problem on their hands.

Young Republicans, in particular, are not aligned with many Republican values – especially not Moore’s. Presently, there is an effort to remove the Alabama Young Republicans from the state Republican Steering Committee for rescinding their endorsement of Moore. This generational rift will only worsen if the divide between the grassroots and the mainstream wings of the party cannot be mended.

Democrats may use this opportunity to begin digging themselves out from rubble that is their state party. They should begin with disaffected, young, better-educated and suburban voters.